McGill Climate and Large Scale Dynamics Group

Opportunities

Undergraduate

- If you are interested in working with me over the summer, please reach out to me by early February 2026. It seems early, but there are some awards that will have application deadlines in February or march.

Graduate

- I am not currently accepting graduate students for 2025 or 2026.

Postdoctoral Fellows

- Please reach out if you are interested in a working with me as a postdoc.

- McGill Postdoctoral Funding Oppurtunities

Teaching

Winter 2024 - ATOC 557 Statistical Research methods

- https://github.com/rfajber/ResearchMethodsCourse

Fall 2024 - ATOC 531 Climate Dynamics

- mostly posted on myCourses

- some lab material available at https://github.com/rfajber/ClimateDynamicsCourse

Winter 2025 - ATOC 215 Oceans, Weather, and Climate (Intro Dynamics)

- notes posted on myCourses

Group Members (Work in Progress)

Current

- Perla Gonzalez (PhD): Stratopsheric Water Biases in Climate Models

- Jiechao Zhu (PhD): Surface Water Mass Transformation and AMOC

- Phillip Boulanger (MSc): Age of Water Vapor Tracers

- Nicolas Cloarec–Rouat (Exchange MSc Student): Effects of Resolution on Air-Sea Fluxes

- Claire Hawley (SURA Undergraduate student, with Juliann Wray): Properties of Fronts in Eastern North America with NcCut

- Jonah Davidson-Harden (USRA Undergraduate student): Tracking Convectively Processed Water Vapor in the UTLS

Former

- Gabriel Lach (CSA group summer student, Honours project): Coupled Extratropical Cyclone and Mesoscale Convective Systems in Observations

- Jelena Collins (CSA group summer student, now PhD student at Yale): Wildfire Smoke dynamics with the Hysplit model

- Elliot Joukakelian (Physics and Computation Honors Thesis, now Scientific Code Developer at ECCC): Data Assimilation with Passive Tracers in a Simple ODE model

Research Topics

Below are a list of some of the topics that I am actively working on. Please feel free to contact me if you are interested in discussing further.

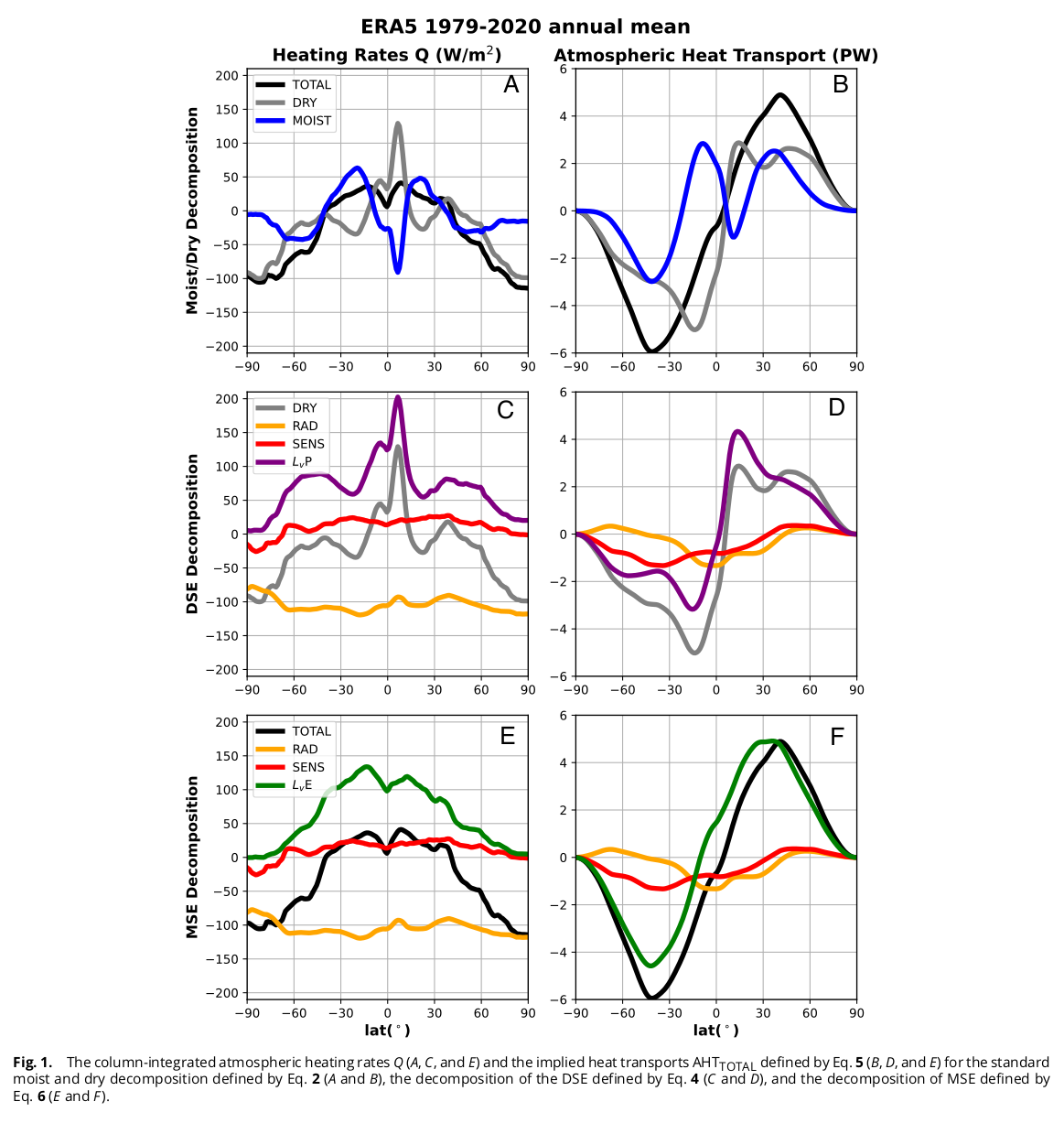

Evaporation and the Dynamics of the Water Cycle

Evaporation is a massive transfer of energy from the ocean to the atmosphere, and has large equator-to-pole gradients. An immediate consequence of this is that the distribution of evaporation is crucial to the heat transport of the atmosphere and ocean, and couples the two of them together. Also, the distributions of evaporation and precipitation are important for maintaining the cycling of water from the ocean to the land, which is important for humans and natural ecosystems. I am interested in understanding what controls evaporation, and how biases in evaporation are linked to biases in heat transport and precipitation.

Recent Publication: Fajber, Robert, et al. “Atmospheric heat transport is governed by meridional gradients in surface evaporation in modern-day earth-like climates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120.25 (2023): e2217202120.

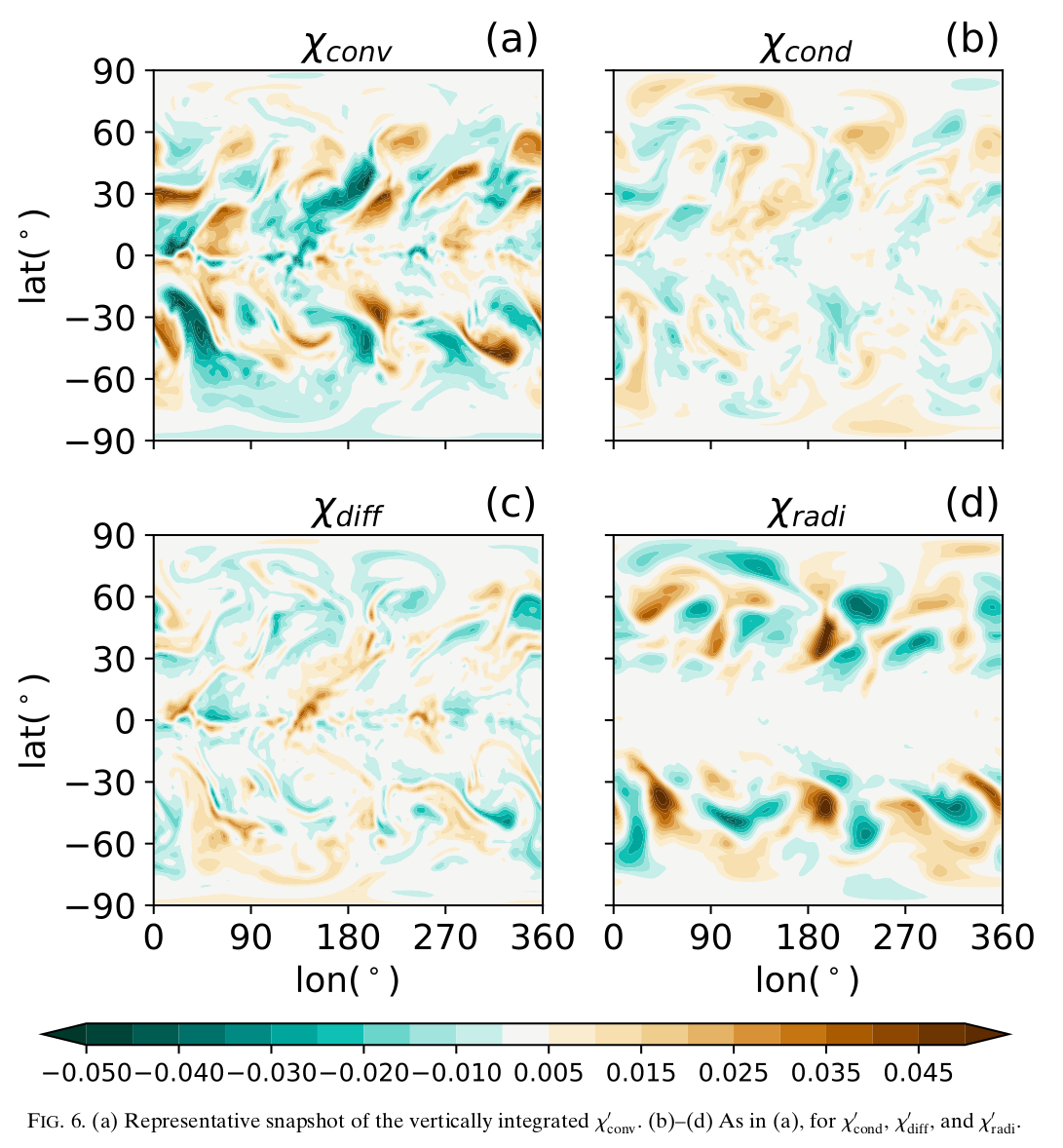

Diagnostics of Atmospheric Transport

The transport of heat and moisture in the Troposphere is complicated by the fact that the transport is non-conservative. For instance, condensation of air parcels removes moisture and adds heat to the dry component of the air. This heat and moisture transport can play an important role in connecting distant regions together, and diagnosing it properly is important for understanding the remote effect of atmospheric moistening and heating on both the mean climate and extreme weather anomalies. To better understand this transport I have been working on using “tagged tracer” methods, which account for both the transport and non-conservative effects of heat and moisture transport. Recently I have also become interested in the transport of smoke from wildfires.

Recent Publication: Fajber, Robert, and Paul J. Kushner. “Using “heat tagging” to understand the remote influence of atmospheric diabatic heating through long-range transport.” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 78.7 (2021): 2161-2176.

Sea Ice

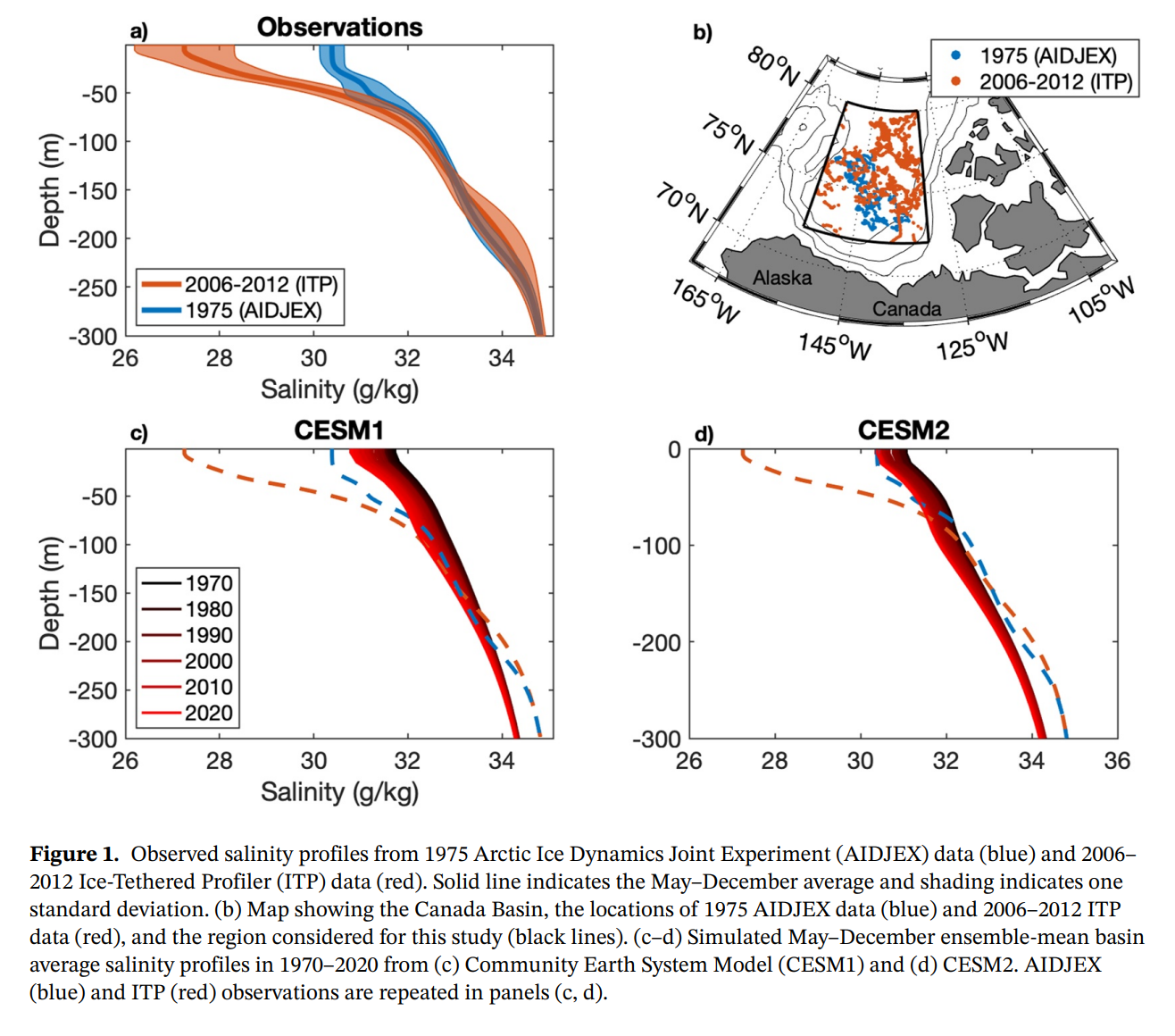

Since the upper arctic ocean is so close to freezing, its density is controlled primarily through salinity. Since sea ice is mostly fresh water, freezing and melting sea ice changes the density of the ocean below it, and links the stratification of the upper ocean to the sea ice. Along with Erica Rosenblum I have been studying the connection between upper ocean stability and sea ice in climate models, and found that the climate models do not reproduce the relationships found in observations. Further understanding these changes is an active area of research.

Recent Publication: Rosenblum, Erica, Fajber, Robert, et al. “Surface salinity under transitioning ice cover in the Canada Basin: Climate model biases linked to vertical distribution of fresh water.” Geophysical Research Letters 48.21 (2021): e2021GL094739.